Jesper Kouthoofd & OK Go’s Damian Kulash discuss the revolutionary OP-1 synthesizer

Dream Machine

Teenage Engineering’s OP-1 is a synthesizer for a new generation. The portable music workstation is a combination synthesizer, sequencer, multi-track recorder, sampler, drum machine, mixer, and controller. And whether you’re a professional musician or a complete musical novice, its clean design and graphic interface make it fun and accessible, and its continually updated operating system means that every few months, the OP-1’s creative and technical arsenal adds even more bells and whistles.

OK Go’s Damian Kulash—who had the opportunity to use the synth on the band’s recent album—sat down to speak with Teenage Engineering’s Jesper Kouthoofd to discuss exactly what makes the OP-1 so special, his own inspirations, and the importance of timing—no matter what you do.

*Edited transcription below.

Damian Kulash: Hi.

Jesper Kouthoofd: Hi! Perfect.

DK: We are recording. It’s happening. I am Damian Kulash from the band OK Go, and you are?

JK: I am Jesper Kouthoofd from Teenage Engineering.

DK: And Teenage Engineering are the geniuses that have made the OP-1 among other things.

JK: This little machine here [presenting synthesizer].

DK: That little machine; that is my favorite synthesizer to have probably existed ever, but certainly in the last 25 years.

JK: Thank you very much.

DK: Really. I do not heap this type of praise on people often. It is really an amazing piece of engineering and design. I don’t have one with me here right now because I’m at Ars Electronica in Linz. And I’m reaching you in Sweden, I presume?

JK: Yeah, this is where I live; actually my bedroom. I live in an area called Old Town, which is the oldest part in Stockholm, so that’s why you see some paintings on the wall from the 16th century.

DK: So those are genuine 16th century paintings back there? Wow, that’s incredible.

JK: Not all apartments have that, but a lot of them [do] in Old Town.

DK: Well, I’m in a cubicle.

JK: You’re in Austria, right?

DK: Yeah, I’m in Austria. We are trying to come up with some fun projects to do using robots and colors and space and music.

JK: Ok, cool.

DK: So, can you summarize for people—non-musicians—why the OP-1 is so awesome?

JK: What I like about it, why we did it from the very beginning is that we really wanted to create a machine—our dream machine—with everything in one unit: the synths, the drum, the sampler, the tape. So it’s a little bit how you worked in the ‘80s, with a four-track recorder, but digital.

DK: What I find amazing about it is that it seems to me like maybe 20 years ago, maybe [in the] early ‘90s, digital technology got to the point where basically every known type of synthetic sound could be in one box.

JK: Yeah.

DK: They’re pretty good at modeling analog synthesizers with digital ones and combining with every sort of digital sampling and all that kind of stuff. So really, every synthesizer since then has mostly been a change in user interface.

JK: Yeah.

DK: I used to use the Kurzweil K2000; it was an incredible synthesizer and an incredible sampler. And it had a manual this thick, and if you spent a year learning it, you could make pretty much every sound you could dream of.

JK: Mhmm.

DK: And what’s amazing about your machine is not only the advances in how well manufactured it is, how well designed it is as a physical object, but that the user interface has four color coded knobs, and a beautiful OLED screen . . . each page is color coded so that you always have four controls, and you can get from the outer level, where it’s really easy to just [for example] push some sounds in and get a piano to come out, to the deepest level, where you are able to make granular synthesis and make these incredibly crazy sounds that no one could have dreamt of 15 years ago.

JK: Haha, yeah [holding up the synthesizer]. Here’s the color coded mixer, and the knobs here.

DK: And it’s just so beautiful and so simple; it’s really about making choices—

JK: Yeah, I would say that the hardest part was trying to make it as simple as possible to use—only using four knobs. You look at other synthesizers today, and they have like 100 parameters. So our strategy here was that we really wanted, you know, when you turn a knob like this [demonstrating with sound] . . . But our strategy was that when you turn a knob, you should hear the difference. Because [with so many of the other] new machines, you can turn a knob, or maybe you can turn like 10 knobs, without hearing any difference . . . so we really wanted this kind of instant [effect].

DK: Well, you’ve succeeded brilliantly! So, the synthesizers from the ‘60s through to the present, but especially the sort of early years of synthesizers, had hundreds of knobs, and like you said, you can twist half of them and nothing will happen until you twist the other half in the right order.

JK: Exactly.

DK: If you have to be a scientist the whole time you’re making music, you wind up making a very different type of sound than you do if you sort of stay in the right-brained place, where you are responding just to the emotion of something.

JK: Mhmm.

DK: So what really differentiates a synthesizer by one company from a synthesizer by another, especially in the last 15 years, is probably just which sounds come up quickest. You know? And so the fact that you are always able to change what you’ve got, dramatically, with what’s in front of you, it makes it really a very sensual instrument.

JK: You’re right.

DK: Tell me a little bit about your history. Did you come from making music?

JK: Not at all. Actually, I was a graphic designer from the start. My brother used to work in a music store, in the early ’80s, when all the Roland machines came—the 303, the BOSS pedals, the Portastudio and all that. So I would say that our background was that we had played around with those machines in the early ’80s, everything from the VL-Tone to the Roland machines; and if you look really carefully at the OP-1, you can see traces of that.

DK: Yeah.

JK: The four-track is obvious, but one of the first sequencers we did was this; it’s called endless step. This is actually based on one of my favorites synths, the Roland JX-3P, which has a really, really simple step sequence. I’m not sure if you have tried it, but you just press, and enter the notes and then—

DK: And then it plays it.

JK: Yes. And I love that kind of direct control. And the sub is from this old Casio; it’s called SK-10, right?

DK: Yeah, there was an SK-1, an SK . . .

JK: Yeah . . . So it’s a little bit mixed with all the great machines from that period, together with this new technology, like the OLED display.

DK: To a non-musician—just since I know a lot of people who will be watching this are design people and not necessarily musicians—every synthesizer that has existed since the ’60s has the same four controls that you see on that page, and almost none of them have a graphical interface that actually makes it feel human.

JK: Exactly, and I would say even more than software like Logic and stuff like that, [which] have . . . a graphic illustration like this, but it’s not connected to knobs. You’d have to point with a mouse, and it’s a very different experience than turning four knobs and controlling each individual curve. I really love that.

DK: It’s also the only synthesizer that I know of that has an accelerometer in it.

JK: Yeah, exactly.

DK: When I first saw your synth, it basically felt like I was viewing a generation ahead of Apple products. You know when you see something and you’re like, “God, that’s so obvious, that’s exactly how that thing should be made.” And what really stuns me is that, you know, Apple of course does know what’s coming 15 months down the line because they’ve . . . uh oh, we’ve got a friend! [laughing]

JK: Ah, my daughter, Ivana. [Kouthoofd’s young daughter runs in background of video, holding a guinea pig.]

DK: Hi, Ivana!

JK: [Swedish to his daughter] . . . Yeah, that’s, the accelerometer . . . The extra element that made it possible is that . . . we are a small group of friends that started Teenage Engineering, and we actually started discussing this machine in ’99 or 2000, but the technology, it wasn’t really there; the batteries were heavy, the processors were not fast enough, and—

DK: The screen wouldn’t have been high enough resolution . . .

JK: Exactly, and . . . there weren’t really any commercial label accelerators at that time either. So a lot of things happened when the mobile phone developed. And so basically all the components in the OP-1 are based on mobile phone components like the OLED display, the processor, the battery technology, the accelerometer and stuff like that. It’s really interesting for us; it was this great axis of time and technology.

DK: Right; all these great ideas you had were possible all at once.

JK: Exactly. I’ll turn this off, but this is the accelerometer. [plays accelerometer] And the great thing is that you can connect that to any parameter in the synthesizer.

DK: Yeah. My band has just finished a record—two weeks ago—and while we were writing the album, I discovered your synthesizer. And I think every single song has at least two tracks of that; some of them are like all tracks of that.

JK: That’s great.

DK: And I’m not even a very good pianist. Most synth-players—up until a few years ago—were people who could actually play a piano, you know? And this is such a visceral instrument; you can shake it to make it do something else. And it’s crazy to me that that’s not . . . I mean, why do guitars not have accelerometers in them? If everyone’s going to be doing this [motions swaying back and forth], it just seems like so many good ideas in one small package.

JK: Yeah, exactly. But I think also when you start from scratch, it’s easier. If you start from scratch in a really nice timeframe, when a lot of new technology comes, it’s easier to adopt it, because you don’t have really any history. I used to work with another synth company called Elektron on the West Coast and Sweden. They have been around for 10 years now, so it’s much, much harder for them to adopt new technology because their engines, all their software, all their code is written on a really old processor. Sorry Elektron for saying this. But it’s much, much easier for us to start from scratch.

DK: I hadn’t thought about that. I went to visit NASA recently, and the last of the space shuttles was still in the bay; they were about to move it out to California. And they walked us around and we were looking all this amazing technology. And they’re like, you know this runs on 386s [32-bit microprocessors introduced by Intel in 1985] . . . So, basically, the computer in there is less powerful than your cell phone, because to retool the entire machine was more expensive than always just one little step up. And suddenly you’re 25 years out-of-date, because all you’ve done is [make] tiny little jumps.

JK: Yeah, exactly.

DK: And Teenage Engineering has designed other products before, right?

JK: No, not our own products, but we did consultancy work for different brands and products . . . We experimented with a lamp, just because we wanted to learn some basic mechanical engineering and manufacturing, so we did that as a test project.

DK: So that was a test project, but you already knew you were making the synth at that point?

JK: Yes, it was parallel. With the lamp, we started to understand how to work a new machine, aluminum, and steel—all that kind of stuff.

DK: Sure.

JK: And we also had to buy some expensive CAD software and learn that.

DK: So you started as a graphic designer, but you worked in fashion design as well, is that right?

JK: I started a fashion company in ’96; I left that in 2003.

DK: What fashion company was that?

JK: It’s called ACNE. We did a lot of other stuff as well. We had a game community called Netbaby; not sure if you remember that one, but it was part of the first wave of shockwave games . . . So, yes, we did a lot of stuff.

DK: There was an ad agency that ran through ACNE too, right?

JK: Yeah, we had an ad agency, the game stuff—that was almost 30 people working on those shockwave games—and a fashion company and a film production company, so also direction of commercials . . .

DK: You and I have never met in person, but every time I go somewhere someone asks me if I know you because they think, “Oh you’re just like this guy Jesper,” and generally it’s because I work as a singer in a rock band but also a director and also as a zig and also as a zag. I generally sort of feel like if I hear a good idea I just want to chase it, no matter what direction it goes.

JK: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

DK: So I’m fascinated to hear your story, because it seems to me like you’ve made this amazing thing, but I don’t know how you decided [to pursue it, especially] when you’re in the middle of producing films, directing videos—I’ve seen some of the commercials you’ve directed, which are genius—and of course you had a fashion company, you had a game community. How did you wind up deciding that this is what you wanted to make?

JK: To be honest, I’ve always used advertising as a cash cow for other stuff . . . I really like to be in the creative business, but at some points you really feel restricted and you feel at least totally uncreative. And so it’s like you need to let your creativity, you need to put that on other stuff that is totally free, and that doesn’t have any clients or people who are going to tell you what’s good or not. So I would say that advertising has been a really good cash cow.

DK: But it takes so much courage to turn down the expensive job that will just make another advertisement, to invest 10 years to make a product that may never come into existence.

JK: It’s not easy. I would say, for me, it’s not that hard because I’ve worked for so many years now. I started in the advertising business in ’91 as an art director, and Sweden is not that big, so it was kind of easy to create a name for [myself].

DK: Sure.

JK: For me, it’s always been harder to find friends and partners to do this with, because maybe they really depend on consultancy work; but for me I know that I can take a break for at least a year, and go back to the advertising business if I need. I have that insurance in a way. But it’s always hard to set up the first team of friends . . . it’s like starting a band, I guess, as you know, to convince them that it’s a really great idea.

DK: Starting a band is actually not a really great idea. [laughs]

JK: Yeah, but still you managed to do that! But setting up the team, and getting all those great people on board, is always really, really tricky and hard; but when you’ve done that, then it’s just hard work I would say.

DK: A lot of times when you go from being a one person company to a 10 person company or bigger, you start with all these creative ideas and you have to do all the bullshit work also, and then eventually you have 10 people and now you just have more bullshit work and no creative ideas.

JK: Exactly.

DK: Last week, when we tried to get together over Skype, you couldn’t because you were deep in China. I assume you were at a manufacturing plant or something?

JK: Mhmm.

DK: Do you find you are able to keep the creative spirit alive even with the huge success of the company?

JK: I’m not sure if it’s a huge success at this point, but for me, I really try to stay creative and true to my roots. And I’ve done the mistake, especially with the company I had before, you know, where you try to be a manager and do all the boring stuff and, finally, you lose it.

DK: Right.

JK: So this time, I’m really careful about still doing a lot of hands-on stuff, everything from the website to the product design to the packaging, because that’s what I love to do. I hate sitting in long meetings or even interviews; I don’t like that [laughs]. I usually work late nights at home, and this is what I love to do, just sit in front of the computer and come up with these small ideas and convince the team that [they’re] good . . .

DK: What’s the next small idea?

JK: We have a lot of small ideas. We are working on a speaker now, with a built-in computer and a wireless protocol . . . It’s quite interesting to use the exact same approach on a very different product. I think the most obvious result of that is we have designed a remote that is a little bit like this in size [holding up a Swedish tobacco canister]. Because when I get home and I want to listen to music, I don’t want to pick up my mobile phone; I just want to press a big play button and have something come out of the speakers. It’s a little bit like the four knobs on the OP-1, but on a completely different product.

DK: I saw some early pictures and prototypes of it, and it seems like it’s based on an old Swedish speaker, right, that points upwards?

JK: Yes.

DK: It seems similar to the OP-1—you’ve taken something that was amazing the first time and re-thought it for the new generation.

JK: Every project is different, in a way, because we felt that to create a really good speaker, it’s like [you need] 10, 20 years of experience doing that. And we are big fans of this old Swedish speaker guy—his name was Stig Carlsson—he did a lot of avant-garde speakers. I actually collect them. You see a large model here [pointing to speaker]; that’s what is called OA-52. It’s a little big, but it points upwards and so it reflects the sound in the ceiling. We didn’t want to go into that area and spend 20 years learning to build a speaker, so we teamed up with those old guys that still work with that and added what we are doing best. It’s also what I liked about every product, that you can adopt the same principles as an earlier one, but you also have to really approach it in a totally new way.

DK: Sure.

JK: How to make a speaker from 1974 fresh again; it’s kind of hard.

DK: And of course there’s a lot of competition in that space. Everyone’s making a wireless speaker these days.

JK: Exactly.

DK: To come up with something people really need is—

JK: And that sounds good. That’s why we took that; we could design from scratch and put a nice design to it, but we really cared about the sound.

DK: I’m excited to hear it. Obviously, you’re inspired by designers of the past; you said you collect speakers from the ’70s. Would you say you take a lot of inspiration specifically from the design community? What inspires you in general?

JK: I can show you! I have one of my favorite all time-designers here [holds up monograph of Italian industrial designer Joe Cesare Colombo].

DK: Ah, Colombo! As you might imagine, my wife and I have that sitting right in the middle of our living room.

JK: I really love this. It’s simple, but still very sexy in a way. What I like about especially Italian design, is that they have these kinds of design principles like the Germans, but they also add passion and sexiness to it.

DK: And playfulness.

JK: Exactly.

DK: Modernism, it seems like, especially in Italy, was able to retain a sense of play. You know, right now, being in Linz, you see a lot of strict, Northern European, cold lines; you wind up with a sort of hospital feelings a lot of times.

JK: Yeah, exactly.

DK: And Italians manage to keep things joyous and human.

JK: And also when you compare it to Swedish design; I think Swedish design, in many cases, is quite boring, or a little bit restricted—like it should be white and this kind of light wood . . . and I think Swedes in general are a little bit scared of using color, so we really aim to use a lot of color in our stuff.

DK: Yeah, I’ve never met anyone with a drier sense of humor than Swedes, you know.

JK: Ehh, but I would also say my father is an architect and he is Dutch . . . and Dutch design is a little bit of a mix between Italian design and Swedish design. You have these clean lines and language, but you also have a little bit of attitude.

DK: It sounds like you’ve gotten to do a lot of graphics and product design along with the sort of experience design of the synthesizer.

JK: Yeah, I mean, we had to. If you look at the display . . . there’s a reason it’s all black. You see the tape with the black background and simple lines, and the reason we did this is because an OLED display doesn’t draw any power when it’s black pixels.

DK: Oh!

JK: So we saved at least you know, like 30 percent more battery power just by doing lines instead of field graphics, which is kind of interesting.

DK: Can you show us the cow?

JK: The cow, I have it here.

DK: There’s a brand new operating system for the synthesizer, which, by the way for non-musicians—

JK: [holding up synthesizer] You see it here.

DK: Yeah, you can kind of make it out. Oh, I love the cow. She makes such a beautiful sound. One thing that is amazing about this synthesizer also is that, like a cellular phone, it’s operating-system based. So every six months I get a new operating system from you, and it’s got, like, three new effects in it, and all sorts of new tricks and toys, and all the things that we wished were in the last version—which never happened with a synthesizer from ten years ago.

JK: You don’t come up with all these ideas when you start, but it’s growing . . . many of the ideas that we started with are five-seven years old. I think really good ideas need time to develop, so that’s why we always experiment.

DK: And it just seems you’re able to respond so much more if you see your tool as a platform, not as a final product.

JK: Exactly, it’s much more interesting in a way.

DK: I wish I could do that with records in a way. Like we’ve just finished a record, and now we have to figure out how to get these songs out into the world. And I’m so excited for everyone to hear them, but I also wish that once they got out there, they could keep growing . . . We’ll figure out a way!

JK: Mhmm. Also, a lot of ideas can be really creative, but I think the hard thing sometimes is to make them useful . . . you and I have discussed some ideas for future stuff, but I would say that the trick is to make it really useful . . . [holding up his notebook] this is a typical page; I’m moving it a little bit so you can’t tell exactly what it is, but . . .

DK: Wow, I wish my notebooks looked like that.

JK: I do a lot of these sketches and other people do it as well, but then I also have to convince the programmers that this is a good idea. If they don’t like it, then they won’t code it for me. So it’s a really nice filter, and it’s not easy; sometimes I really have to try hard, sell it hard to them to make it happen.

DK: Sure. The band is a pretty similar operation . . . you think an idea is great, but if the other guys don’t, then it’s never going to happen.

JK: Exactly. That was actually the case with the cow. The programmer didn’t want to do it; he thought it was a silly idea. But I explained it to him—it was a brilliant idea, you have four different bellies in the cow and you have each chamber—and finally he understood.

DK: Yeah, and again, it should be explained to non-synth-users: That wasn’t just a pretty display; there are four different filters and it’s a highly responsive, incredible filtering sound you can’t get from any other machine.

Listen, thank you so much for your time! Congratulations on changing the world of synthesis, and I hope to talk to you again soon!

JK: Thank you so much!

*This interview has been edited and condensed.

-

Introduction by

-

Anna Carnick

Als ehemalige Redakteurin bei Assouline, der Aperture Foundation, Graphis und Clear feiert Anna die großen Künstler. Ihre Artikel erschienen in mehreren angesehenen Kunst- und Kulturpublikationen und sie hat mehr als 20 Bücher herausgegeben. Sie ist die Autorin von Design Voices und Nendo: 10/10 und hat eine Leidenschaft für ein gutes Picknick.

-

-

Interview by

-

Damian Kulash

-

Designbegeisterte hier entlang

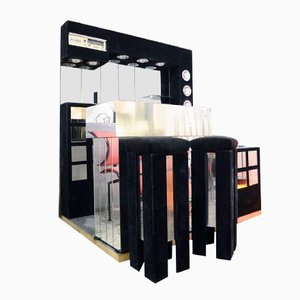

Italienische Bar mit Radio, Kühlschrank & Zwei Hockern, 1960er

Modulares Italienisches Sofa mit Ecktisch & Radio, 1970er

Vintage Atelier 1 Stereoanlage von Dieter Rams für Braun

Dänischer TV & HiFi Konsolentisch von FM, 1960er

Rundes Vintage Radio von Weltron

Tischradio RT 20 von Dieter Rams für Braun, 1961

Radiologie Stehlampe von Siemens, 1930er

Italienische Bar mit Beleuchtung, Kühlschrank, Radio & Zwei Hockern, 1960er